Each year on November 10 in Silver Lake, Minnesota, a long-retired lighthouse is brought back to life and sends forth a piercing beam of light, and in Detroit at the Mariners’ Church, a bell rings out. It tolls six times now for reasons that are rooted more in politics than in memory, but it used to ring twenty-nine times. Each sound of the bell memorialized one life lost on that most famous of Great Lakes freighters, the SS Edmund Fitzgerald.

All of us have probably heard the haunting melody and moving lyrics of Gordon Lightfoot’s 1976 song, written both to memorialize and to pay tribute to the ship and her crew. The song is wonderful, but while most of it is accurate, it doesn’t tell the whole story. Neither does anyone else, at least not very often, now that the wreck has faded into history.

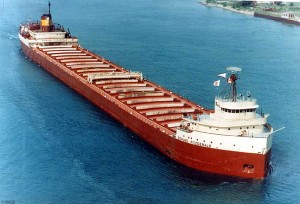

The laker called the “Mighty Fitz” was a behemoth when she was built in the late fifties. An investment property of the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee, she was designed to be the largest vessel plying the Great Lakes. At 729 feet from stem to stern with a 75 foot beam, she wasn’t the biggest in 1975, but she was of well above average size for a laker. Despite her size, in keeping with Great Lakes tradition, she was referred to as a boat, not a ship.

She had but one purpose, which was the transportation of processed taconite pellets. These balls of concentrated iron ore are the lifeblood of the steel industry, and nowhere in the U.S. is taconite more abundant than in Minnesota. Lakers like the Edmund Fitzgerald could load up their holds at ports in Minnesota or Wisconsin, then profitably and economically transport the ore to any of dozens of iron works situated around the Great Lakes.

Like most lakers of the day, the Edmund Fitzgerald had cabins at her bow and stern, with the bridge situated atop the bow. Between the cabins lay a flat deck covered with loading hatches. These huge openings with removable covers allow easy loading and unloading of the pellets by dockside machinery. The hatches are each twelve feet by fifty-four feet in size. A crane was required to remove and replace the hatch covers, which were secured to their openings by clamps that had to be laboriously re-secured after loading was complete.

Like most lakers of the day, the Edmund Fitzgerald had cabins at her bow and stern, with the bridge situated atop the bow. Between the cabins lay a flat deck covered with loading hatches. These huge openings with removable covers allow easy loading and unloading of the pellets by dockside machinery. The hatches are each twelve feet by fifty-four feet in size. A crane was required to remove and replace the hatch covers, which were secured to their openings by clamps that had to be laboriously re-secured after loading was complete.

Captain Ernest McSorley was the captain of the Edmund Fitzgerald at the time of her demise. When Lightfoot describes him as “well seasoned,” he’s not kidding. McSorley had been the master of nine vessels over his 40 year career as a mariner; he had assumed this, his tenth command, in 1972. At 63 years of age, this veteran of both lakes and oceans had earned the respect of his peers and his men alike. He was known in particular to be highly proficient at handling large vessels in foul weather. A Canadian by birth, McSorley lived near Toledo and had planned to retire once the 1975 shipping season was over.

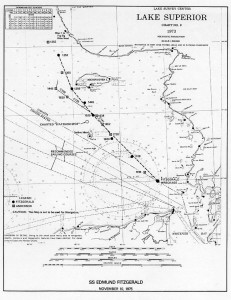

On November 9, 1975, a Sunday, the Edmund Fitzgerald departed from Superior, Wisconsin, loaded with taconite for a steel mill near Detroit (not Cleveland, as Lightfoot mistakenly wrote.) As they moved out onto Lake Superior in the treacherous, unpredictable weather of November, all aboard knew there was a chance they’d encounter a gale, one of the strong, unpredictable storms that Great Lakes captains call November Witches.

A second laker, the Arthur M. Anderson, fell in behind the Edmund Fitzgerald for the crossing, and the two set off at 13 knots bound for the locks at Soult Ste-Marie.

The storm hit the next day, with high winds and ten foot seas by 7:00 AM. Â It was a witch by anyone’s standards. Building quickly, the winds reached 43 knots by 3:20 PM, and waves topping 30 feet in height were battering the boats as they tried desperately to reach safety.

Heavy snow soon dropped visibility to near zero, and hurricane-force gusts slammed the vessels. No men were allowed on deck; the waves and wind were strong enough to wash even a well-secured man overboard, and in these conditions, a life vest was little more than a cruel joke.

Heavy snow soon dropped visibility to near zero, and hurricane-force gusts slammed the vessels. No men were allowed on deck; the waves and wind were strong enough to wash even a well-secured man overboard, and in these conditions, a life vest was little more than a cruel joke.

By 3:30 in the afternoon, the situation looked dire indeed. The Edmund Fitzgerald’s two bilge pumps were working furiously to discharge water which was flooding in, presumably through damaged ballast tank vents. The radar was damaged and inoperative, and the boat was listing slightly. The Anderson was doing somewhat better, and still had functioning radar. Within an hour or so, the Fitz slowed to allow Anderson to catch up, and McSorley asked Captain Jesse Cooper for help with radar coverage.

The vessels, at this point, were tantalizingly close to the relative shelter of Whitefish Bay. McSorley put out a radio call to any vessel near Whitefish Point, inquiring about the radio beacon there. The ocean freighter Avafors answered, and advised that the beacon appeared to be down. McSorley advised the Avafors, “I have a bad list, lost both radars, and am taking heavy seas over the deck. One of the worst seas I’ve ever been in.”

The end came quickly, when it came. At shortly after 7:00 PM, a series of huge rogue waves hit the Anderson. The crests of the waves were so high they could be clearly seen on the Anderson’s radar. They slammed into the Anderson with such force that they damaged lifeboats hanging 35 feet above the waterline. The waves came out of the northwest, and Cooper saw that they were headed directly toward the Fitzgerald. Cooper immediately radioed the Fitzgerald to warn Captain McSorley and check on his status. McSorley reported, “We are holding our own.”

The end came quickly, when it came. At shortly after 7:00 PM, a series of huge rogue waves hit the Anderson. The crests of the waves were so high they could be clearly seen on the Anderson’s radar. They slammed into the Anderson with such force that they damaged lifeboats hanging 35 feet above the waterline. The waves came out of the northwest, and Cooper saw that they were headed directly toward the Fitzgerald. Cooper immediately radioed the Fitzgerald to warn Captain McSorley and check on his status. McSorley reported, “We are holding our own.”

Those were the last words ever heard from the SS Edmund Fitzgerald. At 7:25 her target disappeared from the Arthur M. Anderson’s radar.

Theories abound about what happened, and how the ship could have gone down so quickly without a flare, a distress call, or a trace on the surface. Early theories held that the boat must have broken in half on the surface. She was so long that it was possible for her bow and stern to sit on two wave crests while her mid-keel was out of the water; the alternative was also possible with the ship high-centering on a single wave crest, her bow and stern suspended over the troughs. Only after the wreckage was discovered and surveyed was this theory finally put to rest. The two halves of the ship rested only a few yards apart, making a surface breakup extremely unlikely.

The US Coast Guard report held that the ship took on water due to improperly secured hatch covers. The theory was that the covers allowed water to slowly flood the cargo holds, eventually resulting in a loss of stability and buoyancy that sent the ship to the bottom.

The Lake Carriers Association, the trade organization that represented a dozen or more shipping companies including the operator of the Edmund Fitzgerald, didn’t like this theory because it put the company’s employees at fault. While it was well known that laker crews were often less than cautious about completely securing every hatch cover clamp and that the clamps were often broken or damaged, the LCA decided to blame charts instead. They felt it was far more likely that the governments of the two countries had supplied the operators with inaccurate charts. Because of this, they claimed, the Fitzgerald had struck an incorrectly charted six fathom shoal and breached her hull below the waterline. Their theory held that the captain and crew knew nothing of this deep hull damage and cargo hold flooding until it was too late; the vessel had nose-dived directly to the bottom and broken in half on impact.

The Lake Carriers Association, the trade organization that represented a dozen or more shipping companies including the operator of the Edmund Fitzgerald, didn’t like this theory because it put the company’s employees at fault. While it was well known that laker crews were often less than cautious about completely securing every hatch cover clamp and that the clamps were often broken or damaged, the LCA decided to blame charts instead. They felt it was far more likely that the governments of the two countries had supplied the operators with inaccurate charts. Because of this, they claimed, the Fitzgerald had struck an incorrectly charted six fathom shoal and breached her hull below the waterline. Their theory held that the captain and crew knew nothing of this deep hull damage and cargo hold flooding until it was too late; the vessel had nose-dived directly to the bottom and broken in half on impact.

The National Transportation Safety Board initially rejected both the Coast Guard and LCA theories. They eventually backpedaled, agreeing that the boat probably sank due to water flooding in through the loading hatches. However, rather than blaming the crew, the NTSB put more of the blame on the design of the hatch covers and on the storm itself. From their final report:

“The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the sudden massive flooding of the cargo hold due to the collapse of one or more hatch covers. Before the hatch covers collapsed, flooding into the ballast tanks and tunnel through topside damage and flooding into the cargo hold through non-weathertight hatch covers caused a reduction of freeboard and a list. The hydrostatic and hydrodynamic forces imposed on the hatch covers by heavy boarding seas at this reduced freeboard and with the list caused the hatch covers to collapse.”

There were no survivors, and no bodies were recovered. Generally, the bodies of drowned men eventually surface, due to natural decomposition processes that produce buoyant gas. When the water is cold and deep, as it is in the vicinity of the Edmund Fitzgerald’s wreck, the bodies are instead preserved. The Edmund Fitzgerald is now a memorial. No dives are allowed upon her wreck. Lake Superior, in song, legend, and reality, does not give up her dead.

There are twenty-nine men who know what happened that night, and why their ship disappeared without so much as a flare or distress call. None of them can speak. They lie entombed in the broken wreck of their ship, seventeen miles from the safety of Whitefish Bay, in 530 feet of water, in a lake that holds her secrets closely.

In 1995, the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society sought and received the approval of the Canadian government and the families of those lost in the wreck to dive upon the Edmund Fitzgerald and retrieve her bell. The bell would serve as a tangible memorial for the families and survivors of the crewmen. A replica bell carrying the names of the 29 lost would replace it at the wreck.

In 1995, the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society sought and received the approval of the Canadian government and the families of those lost in the wreck to dive upon the Edmund Fitzgerald and retrieve her bell. The bell would serve as a tangible memorial for the families and survivors of the crewmen. A replica bell carrying the names of the 29 lost would replace it at the wreck.

The bell is now part of a memorial located at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum at Whitefish Point. Painstakingly and lovingly restored, it stands alongside a horribly smashed lifeboat, several life rings, and a few other items comprising the only tangible remains of the great vessel claimed by the November Witch.

As Gordon Lightfoot wrote and sang, “The iron boats go, as the mariners all know, with the gales of November remembered.”

Permalink

Thanks Scotters. I was familiar with the song, of course, but I never knew the story behind it.

Permalink

What a moving story. Great writing Scott.

Ugly beast of a boat though: it looks like it wants to snap in two.

Permalink

I’d never heard of this before. I suppose because I was born over here instead of over there, and in december ’75 at that.

Nice vid on youtube:

http://uk.youtube.com/watch?v=8_8s2zsNhSM

I have to with H there; an excellently written piece, Scott. Thanks for the enlightenment (although not of the Buddhist variety!)