I’ve been giving a lot of thought over the past few days to the nature of the music industry. Most of that thought has probably been provoked by the show I’m working on; I’m mixing sound for a local civic theatre production of the musical, “Dreamgirls.” It’s about three girls trying hard to make it in the music world, and along the way it shows us the ugly side of an industry, a side no one sees.

When I took my first full-time radio job back in 1982, I had to sign a document drawn up by my employer, swearing that I would accept no remuneration, no compensation, no gifts and no money from any outside entity to either play or not play any particular record. Every station did this, and every station still does. It’s because of a practice that rocked the radio world starting in the 1930s: payola.

When I took my first full-time radio job back in 1982, I had to sign a document drawn up by my employer, swearing that I would accept no remuneration, no compensation, no gifts and no money from any outside entity to either play or not play any particular record. Every station did this, and every station still does. It’s because of a practice that rocked the radio world starting in the 1930s: payola.

In the idealist’s view, radio in the early half of the twentieth century was pretty simple. Disc Jockeys, the pilots of the airwaves, played the music they liked and thought would be popular; if a record did well, record sales would go up, and the artist would get paid.

The reality was (and is) not quite so rosy. Record companies, having a vested interest in making their artists popular, would make friends with the country’s top disc jockeys. “Make friends,” of course, is a euphemism for showering them with money, gifts, and other inducements. All you needed to get a record played was money, and lots of it. Once the DJ’s became puppets of the record companies, exposure was a simple matter of greasing the right palm.

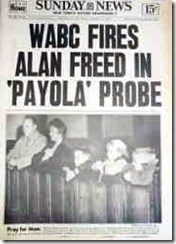

Starting in the 1960s, the government noticed that some of the inducements given to disc jockeys were beginning to involve drugs. That woke someone up, and as payola was investigated, it was discovered that it went further than anyone had imagined. Big names like Alan Freed, Tom Clay, and Dick Clark were all involved in payola scandals that either cost them their jobs or greatly impacted their popularity and credibility. The crackdown intensified.

Starting in the 1960s, the government noticed that some of the inducements given to disc jockeys were beginning to involve drugs. That woke someone up, and as payola was investigated, it was discovered that it went further than anyone had imagined. Big names like Alan Freed, Tom Clay, and Dick Clark were all involved in payola scandals that either cost them their jobs or greatly impacted their popularity and credibility. The crackdown intensified.

Of course, even as payola became less of a standard practice, the success of records still hinged on money, as it does today. Record companies found a way around the law. Independent record promoters were retained by the record companies to carry their message (and their money) to the radio stations. Since the record companies weren’t paying the stations directly, they could insulate themselves from any claim of payola — if a question arose, the promoter would simply take the fall, but it seldom happened. It was less than ten years ago when an FCC investigation determined (and codified) that even this did, in fact, represent payola. Several record companies as well as a few large broadcasting corporations paid hefty settlements while admitting nothing, just to make the bad publicity go away.

So, we might quite reasonably conclude that this is the way the music industry has always operated. The popular artists are the ones who have record companies pouring money into their recording sessions, their tours, their publicity, and their distribution. The struggling artists are the ones who have either small labels or no label at all backing them, and therefore have little money. It’s not about talent. It’s not about artistry. It’s about money.

We could put a federal agent in every record promoter’s office, and have another one guarding the desk and phone of every program director, music director, and radio station owner in the country, and it would still be the same. Getting a record out there, giving it exposure, getting it airplay — all these things cost money. Putting the artist’s face on billboards, posters, and magazine covers costs money, too. People can’t like a record they never hear. Hit records cost money long before they make money, payola or no.

So here’s my question. Why is payola illegal?

Seriously, I know that sounds crazy, but it sounds like we’ve taken the entire basis of mainstream hit music, like it or not, and made it illegal, forcing everyone to do tap dances around complicated regulations in order to do exactly what they were going to do all along. Whether a record company is throwing a few million dollars to jocks or programmers to get a record played, or throwing a few million dollars into a flight of TV ads for that same record, the result is really the same. People who like the music will go buy the record. People who are impressionable and don’t really know what to like will allow either the ad or the DJ to tell them that this is what they should like, and they’ll go buy it. People who don’t like that style of music won’t be influenced by either method.

Either way, money = popularity. We allow candidates for public office to spend as much money as they want (with certain restrictions) on their political campaigns. I can’t quote actual statistics, but I’d be willing to bet that the guy who spends the most money has the best chance of getting elected, provided he doesn’t go on a red-faced screaming rant, claim she can see Russia from her house, or engineer a burglary. Just as in a political campaign, a record’s popularity and success depends entirely on the amount of exposure it gets — in other words, upon how many people hear its message.

In Dreamgirls, speaking of trying to kill a competitor’s record to make his a success, the character Curtis Taylor, Jr., says, “If I can buy a hit, I can buy a flop.” Funding positive campaigns is legal. Funding a negative campaign is legal. Only in the music industry do we pretend that these things are more evil and make them crimes.

Don’t get me wrong. I wish, more than you can imagine, that the success of a record was solely a function of its quality. I wish that the really talented artists, the singer-songwriters, the wonderfully gifted people who are now trapped in the doldrums of the industry, toiling away on small indie labels and dreaming of mainstream fame could achieve it merely by being just that good. New technologies like Internet radio and podcasts have given us new, very accessible distribution channels, but by the same token, they’ve widened the playing field to such an extent that any individual player is all but invisible … and we’re back to needing promotion.

I’m not advocating that we drop all the payola laws. I’m just wondering if it’s not time to re-think what we consider a crime, in light of how hypocritical these laws have become.